The Bronco

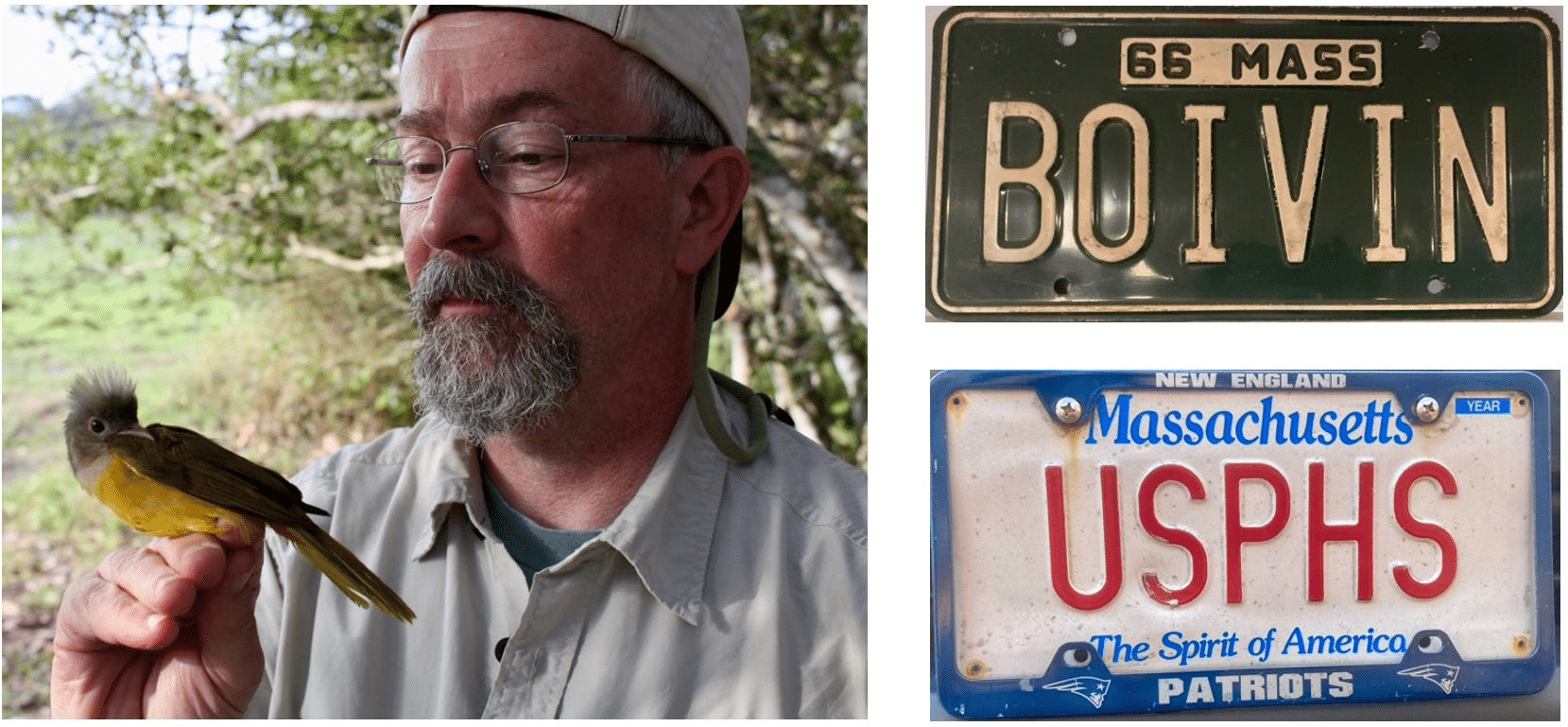

In this installment of Plants & Animals, Bill writes about long-time feathered companion, Sam.

There was a houseguest waiting for us when my wife, Jane, and I returned from our honeymoon. “My hairdresser wanted to get rid of his parrot,” said our friend, Debbie, “and I knew just the home for him.” Something about our existing menagerie–one small parrot (Ralph), one parakeet, one 3-foot iguana, two guinea pigs, a turtle tank, and a fish tank (in a “no pets allowed apartment”, but that’s another story)–must have tipped her off.

So, when we returned from our travels, there he was. Sam came to us as a “bronco”: a totally untamed, full-sized parrot with a beak strong enough to break your fingers. He had come with no pedigree, but he resembled a lilac crowned Amazon parrot.

If Sam and the rest of our animals were going to live and thrive under one roof, Sam needed to be tamed. There was only one problem: He was wild and afraid. Any time I reached into his cage, I had to wear gloves covered in large metal staples–a coat of armor, designed to withstand a bite from a monkey–to protect my skin (and bones!) from Sam’s beak. It took a full year of constant work (and a few bites) to get Sammy to sit on my ungloved hand.

From that point on, our relationship improved steadily, and Sam and I eventually became a bonded pair. Jane could handle him or pet him, but only if I was not in the room. When we moved out of our apartment and bought a house, our parrots (a total of 3 by that time) were out of their cages whenever we were home. They were free to fly wherever they wanted, except for Josie who was unable to fly. Ralph would taunt and antagonize Sam until he got angry and chased her (yes, Ralph was a female). Ralph was smaller and a much more agile flier. One of her favorite tricks was to get Sammy on her tail, and then take him full speed towards a wall where she would veer off at the last second. Sammy, being a clumsier flier, would crash into the wall, much to Ralph's amusement.

Having free flying birds in one's house is a housekeeping challenge. Feathers and dander need constant vacuuming. And, there is the question of poop pickup. Birds cannot be potty trained. They have no anal sphincter and thus, as the saying goes, “it happens.” They had favorite perching spots, like on top of their cages and on a floor-standing perch, so we put papers under those. Fortunately, birds’ bathroom needs are not frequent. You just clean it up and move on, kind of like changing diapers.

As a bonded pair, Sam and I spent a lot of time together. He would follow me around the house and sit on my shoulder, my head, and in my lap. He ate out of my dinner plate and drank out of my glass. I had to be always alert to keep him out of my Jack Daniels. (He was a loud and obnoxious drunk!)

One of Sam’s favorite activities was pruning my "feathers."

To fly, birds need to meticulously maintain their feathers by constantly pruning, or “preening.” They prune their own feathers and those of their partners. Watch a bird carefully and you will see them run their beak along the length of each flight feather from base to tip. Feathers are composed of smaller parallel filaments or barbs. Along those barbs are pairs of smaller, interlocking barbules that link together like Velcro. By running a feather through its beak, a bird can “repair” feather separations by zipping the barbules back together. Proper feather maintenance is essential to maintain flight, which is in turn necessary for self-preservation. That preening also spreads oil on their feathers to create waterproofing so their feathers and skin do not get wet in the rain. (A bird cannot fly if its feathers are saturated.) This is extremely important for water birds like ducks. (A few birds, like cormorants, do not have oil glands - their feathers get soaked. That’s why you see cormorants sitting in the sun with their wings spread out - to dry them for flight.)

Sam and I got good at pruning each other’s feathers. I learned to take his feathers between two fingernails and run up the length of the feather. I could actually zip the barbules together and repair separations. He loved that, especially on his head and neck where he could not reach. In return, he would run his beak the length of a strand of my hair, mimicking the same action. And he didn’t stop at my head feathers. He pruned ALL my feathers–my beard, the hair on my arms, my eyebrows, even my eyelashes! (A few times, while he was pruning my arm hairs, he swung a leg over to straddle my wrist and started humping. That’s where I drew the line…I was not ready to take our relationship to another level!)

One summer, after a day of painting my house, I came in covered in paint spots, including in my hair. That was completely unacceptable to Sam. He immediately commenced cleaning my head feathers, picking out paint where he could and ripping out the hairs where he could not. He was not going to stop until the job was done. I finally had to put him in his cage and go wash my hair.

As long as I was not in the room, Jane and Debbie were fully welcomed by Sammy. They could scratch his head, and he would kiss them. He would even flash his eyes at them. (Human eyes take time to adapt to changes in brightness. Unlike humans, birds have voluntary control over their pupil size. This likely evolved to help them as they flew quickly through the dense forest canopy with rapidly changing light conditions. If they are excited, they will rapidly contract and expand their irises to flash their color. It’s very cool.)

One day, Debbie was enjoying some quality time with Sam as he was on his floor-standing perch. She was coo-cooing him; he was kissing her. He then stopped, tilted his head and lunged with his beak. HE SNATCHED THE CONTACT LENS RIGHT OFF OF HER EYEBALL!!! He then took the lens in his claw, looked at it, snapped it in half with his beak and threw it on the floor. It was as if, all at once, he thought, “Excuse me, you have something in your eye…let me get that for you…You’re welcome.” Debbie said she never felt a thing.

After a few years in that house we completely rebuilt it and included an aviary. The birds were almost always uncaged. One morning I went into the aviary and was shocked to find Sam dead on the floor under his perch. We suspected a sudden heart attack.

We never knew Sam’s true age, but he was an adult when we got him and we had him for about 18 years. I am still amazed that my relationship with Sam progressed from him trying to bite off my fingers to one where I was completely comfortable letting him prune my eyelashes. My relationship with him was probably the most intimate I’ve had with any other animal, except for my wife, Jane.

Many people see birds and other animals as dumb creatures, but the care and companionship that developed between Sam and me is evidence that the relationship between people and their pets goes much deeper.

Bill Boivin is a scientist, retired from 30 years of active duty with the United States Public Health Service. He is a Burlington Town Meeting Member and Conservation Commissioner. He and his wife, Jane, grew up in Lynn and now live in Burlington with their 2 mini dachshunds, 7 chickens, and Maya, a ball python. Bill and Jane have shared a love of nature, gardening, and wildlife for over 50 years. They have fostered, healed, raised, and loved a remarkable variety of animals in their time together. Learn more about Bill.