Respect Your Elders - Know the Facts Before Cutting Down Trees

Think before cutting down trees on your property - they are more important to the environment than you might realize!

Fun fact: Many of the houses in my neighborhood were likely built after vast amounts of fill were brought in to fill in the wetlands and create a beautiful new neighborhood. That was before the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act (WPA), which would have prohibited cutting down trees, bringing in fill, and building homes atop the wetlands. I have often said that if the WPA existed in 1950, half of Burlington’s residences would not exist today. But here they stand, and since they were pre-existing prior to the WPA’s establishment, there was no requirement to restore the previous wetland.

Here’s another fun fact: Trees are among the most massive things that ever lived. A mature oak tree, like you might have in your yard, can weigh 30 – 50 tons. A California redwood can weigh over five thousand tons (10 million pounds). Compare that to elephants at 3 tons, dinosaurs at 65 tons, and even blue whales at 150 tons.

But trees don’t hunt and eat animals. They don’t filter and ingest tons of plankton. They don’t graze over vast plains eating mounds and mounds of vegetation. So how do they achieve and maintain such enormous size? By quietly, efficiently, and patiently sucking up immense amounts of water from the ground and carbon dioxide (including carbon pollution) from the air, using a process called photosynthesis to manufacture nutrients for themselves. By doing so successfully, they slowly build plant material in their trunks, branches, leaves, and roots, month after month, season after season, for many, many years. And as an added bonus, the atmosphere receives clean water vapor and oxygen, both of which benefit the surrounding inhabitants.

Our specimen tree, the Japanese umbrella pine, surrounded by native shrubs: L to R: Summersweet (Clethra alnifolia), the umbrella pine, fothergilla (a member of the witch hazel family), and dwarf lace-leaf Japanese maple

The flooded neighbor constantly uses large pumps to try to remove the water from their yard and pump it into the street. But here’s the rub: When water is pumped from a property into the street, it doesn’t just go away. It goes down the nearest catch basin which then discharges into a wetland resource in somebody else’s backyard. In my neighbor’s case, the catch basin dumps to the property 3 doors away, which is a certified wetland. That reservoir of water extends underground back to his own property. When the groundwater level, or water table, gets high enough, water appears above the surface and floods the yard. It’s a closed loop and a futile effort.

There are two types of wetlands: bordering wetlands and isolated wetlands. Bordering wetlands are connected to a pond, stream, or river and eventually drain to them. Pumping water to a catch basin that empties into a stream just increases flooding to someone else’s property downstream.

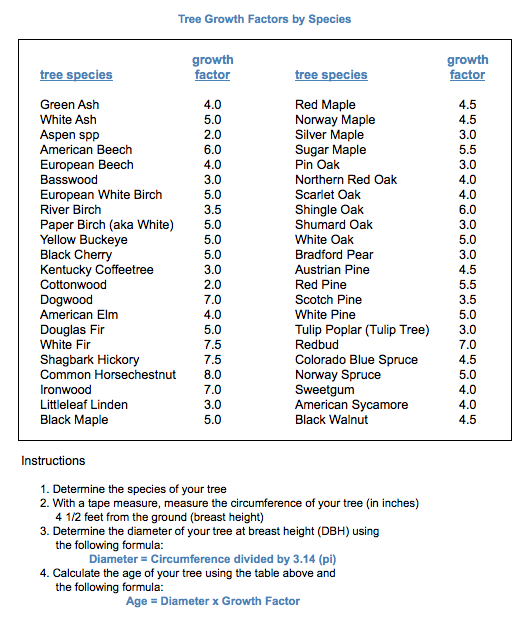

Isolated wetlands do not have such a connection. My yard is part of an isolated wetland. The only way the water level of an isolated wetland can go down is through evaporation and…wait for it…transpiration of trees and plants! Just ten mature trees in your yard could be removing 1000 gallons a day! Think of what my 62 trees are doing and how much more water I would have if I cut them all down! One of the main reasons that the Wetland Protection Act (WPA) establishes a 100-foot buffer zone around wetlands is to prevent clearcutting near wetlands and its resulting impacts. This protects the ecosystem and nearby homes.

In addition to aiding in stormwater management, trees provide many benefits including:

- Providing wildlife food and habitat

- Cleaning our air

- Providing shade that assists in cooling of streams, forests, houses, and paved areas (Proper tree planting can alleviate the “heat island” effect in urban areas and parking lots.)

- Carbon sequestration

- Reducing noise pollution

- Providing privacy from our neighbors (I have a corner lot. My two 15-foot rear setbacks are completely filled with trees and shrubs.)

I’m 73 years old. I love trees, especially trees that are older than me. After finally counting, I realized I have 63 trees on my half-acre lot. These are trees, not shrubs or saplings. And I still have a 1500-square-foot lawn and large beautiful perennial gardens.

On our property we have red oaks, white oaks, red maples, Norway maples, Japanese maples*, white pines, hemlocks, eastern red buds*, ash trees, Eastern red cedars*, arborvitae*, a crab apple tree, a sweet bay magnolia*, a limber pine*, a thundercloud plum*, a sourwood*, and our pièce de résistance: a gorgeous Japanese umbrella pine*. (Those marked with an asterisk (*) represent the 14 of the 63 trees that were planted by the author.)

An interesting side note…we once hired a landscape contractor to help us plant an area with primarily native plants. She brought us two catalogs of native trees and shrubs. One catalog showed plants that exist here now; the other showed plants that existed here before the ice age. She considered them to be “native” plants because they used to live here before the glaciers pushed them out. It may take millennia before they crawl back up here on their own, but they once again can survive here just fine. The sourwood is one of those trees.

Bill Boivin is a scientist, retired from 30 years of active duty with the United States Public Health Service. He is a Burlington Town Meeting Member and Conservation Commissioner. He and his wife, Jane, grew up in Lynn and now live in Burlington with their 2 mini dachshunds, 7 chickens, and Maya, a ball python. Bill and Jane have shared a love of nature, gardening, and wildlife for over 50 years. They have fostered, healed, raised, and loved a remarkable variety of animals in their time together. Learn more about Bill.