Life and Death Down Under

Columnist Bill Boivin solves a mystery—and uncovers an underground graveyard.

If you told me when I became a homeowner that I’d be conducting experiments on small animal carcasses in my backyard, I never would have believed you. Yet there I was, one sunny afternoon, lifting up the edge of an upturned flower pot in search of the tiny body of a (naturally deceased!) shrew I’d put there two weeks prior.

It was gone. And this wasn’t the first time an animal that definitely couldn’t have moved on its own had disappeared. But how?

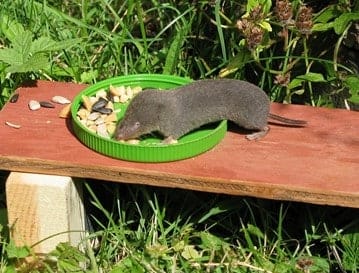

Sadly, small animals occasionally drown in my in-ground pool—mice, chipmunks, moles, voles, and once, even a baby skunk. The most common victim has been the Northern Short-tailed Shrew. Smaller than a chipmunk, shrews spend most of their lives underground, using their very sensitive snouts to detect worms to eat. Since they don’t use their sight much, their eyes have become very, very tiny. So, they have poor eyesight and are attracted to water where they are likely to find more worms. When they unexpectedly fall into a large body of water, they are doomed.

I usually bury the victims among flowers in the yard. But one time I got the idea to put the small carcass behind the woodpile to see if it might decay and leave behind a skeleton. I checked it a week or two later to find that the body was gone without a trace. Probably grabbed by a crow or possum, I surmised.

The subsequent victim went into the same spot, but this time under an inverted flower pot. That way, only bugs could get it. Two weeks later, I lifted the pot expecting to see a cool shrew carcass, only to find the animal was completely gone again. Hmmm, I thought. Well, maybe a clever racoon stole it. So, the following carcass went under the pot with a heavy stone on top. I went out two or three weeks later, removed the stone, lifted the pot…and once again, empty with no evidence whatsoever that there was ever anything there. Now I had a mystery that needed solving!

Thankfully, drowning victims only appeared around once or twice every month at most (And after I put in a small floating platform like this FrogLog with a ramp up to the pool edge as an escape route, fatal incidents decreased considerably). So this process took some time. But I was determined to figure out what was happening to these little cadavers!

Next cadaver: flower pot, heavy stone, and checked the next day…GONE WITHOUT A TRACE!!! My idle detective work had become a mission.

I took the next floater, put it under the pot and stone and checked it in an hour. Voila! It was there and covered with small (about 1”) black beetles. A little research revealed that they were sexton beetles, also known as burying beetles. They were not eating the carcass but burying it as fast as they could. It took them only two or three hours to suck it underground, leaving no trace it had ever been there. Mystery solved!

Why do they bury it? I can think of a couple of good reasons. First, burying it removes it from sight and reduces competition from other scavengers. Second, if they spend time above ground eating it, they themselves could become prey for insectivores such as birds, possums or mantises. So, they get it underground quickly and eat at their own leisure. Another wonder of nature!

Why are they called “sexton” beetles? From Wikipedia: “A sexton is an officer of a church, congregation, or synagogue charged with the maintenance of its buildings and/or an associated graveyard.” These beetles are burying the dead, hence “sexton” beetle.

For the next year or two, whenever I had a small carcass, I left it under the flower pot behind the woodpile for their dining and dancing pleasure. The insects did have a somewhat discriminating palate. Squirrels were too big to bury. They didn’t do birds. Small mammals under about 6” seemed to be their preferred food source.

During this time, we often did daycare for a 5-7 year-old. Being a science geek myself, I encouraged similar interests in her: turning over rocks to look for bugs, looking at things under the microscope, taking her to workshops at Burlington’s Einstein’s Workshop, and one of my personal favorite activities, making her play tic tac toe against me while she was blindfolded. (Numbering the squares one to nine, I would start “X in 3” she would reply “O in 2”, etc. Make that little brain work!)

One day, we decided we would do a little gravedigging. With a bucket and trowels we dug up soil in the area of the sexton beetle activity, brought it to our worktable, and sifted it to see if we could find bones. We did—dozens of them! Tiny little jawbones, ribs, femurs, and entire skulls. What a treasure hunt! We then bleached them and mounted them in paper-lined petri dishes, one for her and one for me. It still is one of my prized possessions.

Backyard osteoarchaeology – who‘d’a’ thunk it?!

Bill Boivin is a scientist, retired from 30 years of active duty with the United States Public Health Service. He is a Burlington Town Meeting Member and Conservation Commissioner. He and his wife, Jane, grew up in Lynn and now live in Burlington with their 2 mini dachshunds, 7 chickens, and Maya, a ball python. Bill and Jane have shared a love of nature, gardening, and wildlife for over 50 years. They have fostered, healed, raised, and loved a remarkable variety of animals in their time together. Learn more about Bill.